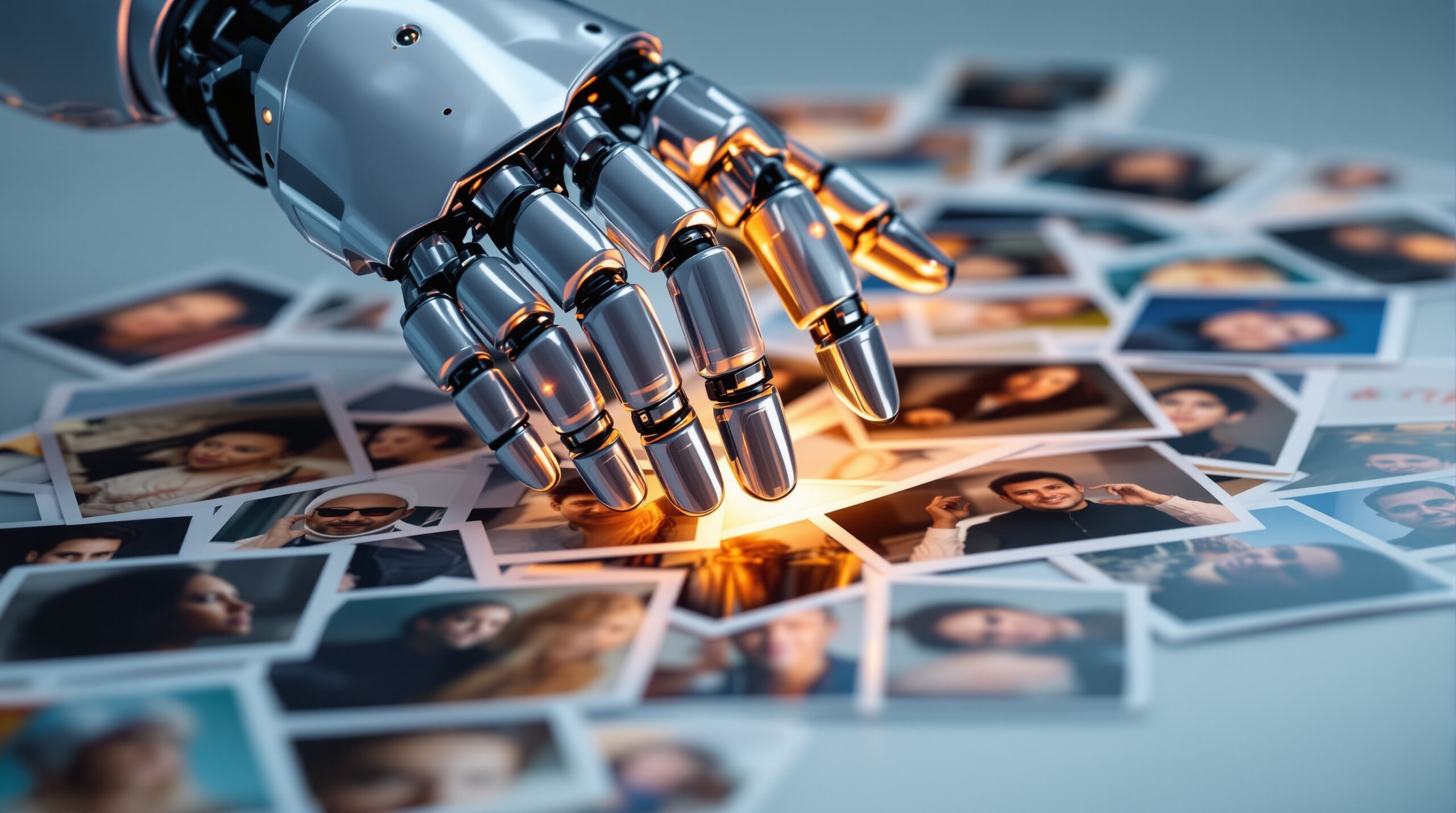

Most professionals assume artificial intelligence will reduce discrimination. Survey data shows 51% of people believe AI will decrease racial and ethnic bias. Yet research analyzing over 5,000 AI-generated images tells a different story—these systems amplify both gender and racial stereotypes across platforms. This gap between expectation and reality creates dangerous complacency as organizations deploy AI for hiring, lending, healthcare allocation, and criminal justice decisions.

The disconnect matters because AI systems now make consequential choices affecting millions of lives. Social bias in these systems is not a minor technical glitch but a systemic challenge where algorithms trained on historical data encode and magnify existing inequalities. Social bias is not eliminated through automation—it is reinforced through patterns learned from flawed historical data. With 55% of both experts and the public expressing high concern about bias in AI decisions, leaders face an urgent mandate to understand how these systems either reinforce or mitigate social bias. The stakes include not just organizational reputation but the lived experiences of people whose opportunities depend on algorithmic decisions they cannot see or contest.

This article examines how AI systems perpetuate inequality, why current mitigation efforts fall short, and what leaders must do differently to ensure technology serves justice rather than automates historical patterns of exclusion.

Quick Answer: Social bias in AI systems predominantly reinforces existing inequalities rather than eliminates them. Algorithms trained on historical data learn and replicate embedded biases, with studies confirming that generative AI tools amplify gender and racial stereotypes across platforms. Most users cannot detect these patterns until bias becomes explicit, making systematic auditing and continuous monitoring essential for responsible deployment.

Definition: Social bias in AI is systematic algorithmic discrimination that produces outcomes disadvantaging specific demographic groups based on race, gender, age, socioeconomic status, or geography.

Key Evidence: According to AIMultiple Research, studies comparing three generative AI tools found that all models reproduce social biases across age, gender, and emotion representations.

Context: This establishes bias as a systemic challenge inherent in how AI learns from flawed historical data, not an isolated vendor problem.

Social bias in AI works through a straightforward mechanism: algorithms learn patterns from data, then apply those patterns to new decisions. When training data reflects centuries of inequality—and it almost always does—the algorithm encodes discrimination with mechanical efficiency. Organizations expect AI objectivity to eliminate bias, but the system simply automates whatever patterns shaped the historical data. The sections that follow examine exactly how this happens across different domains, why current mitigation efforts prove insufficient, and what leaders must do to deploy AI systems that serve integrity rather than perpetuate injustice.

Key Takeaways

- Algorithmic amplification: AI systems trained on historical data encode and magnify existing inequalities, with documented bias in criminal justice, healthcare, hiring, and lending.

- Detection failure: Most users only notice bias when AI shows explicitly different treatment, missing subtle patterns in training data that produce systematic disadvantage.

- Narrow focus: Current bias discussions concentrate on race and gender while overlooking socioeconomic status, geography, age, and linguistic diversity.

- Feedback loops: When AI systems make biased decisions, they create data patterns that reinforce and compound that bias in subsequent iterations.

- Continuous monitoring: One-time audits prove insufficient as deployed systems drift over time, requiring ongoing evaluation to catch emerging bias patterns.

How AI Systems Learn and Perpetuate Social Bias

Algorithms learn patterns from historical data that reflects centuries of inequality, then encode these discriminatory patterns into decisions affecting millions of lives. When datasets contain biased content—as internet-sourced data frequently does—these biases transfer directly into AI outputs with mechanical efficiency. Maybe you’ve assumed that removing explicit demographic markers from training data would solve the problem. It doesn’t. The system does not question whether the patterns it learns are just. It simply optimizes for accuracy based on what the data shows.

Research by AIMultiple confirms that AI systems pick up patterns reflecting social inequalities and amplify them over time through feedback loops that worsen bias unless caught early. This amplification happens because each biased decision creates new data that reinforces the pattern in subsequent training cycles.

The criminal justice system provides stark evidence. The COMPAS algorithm, widely deployed for risk assessment, incorrectly labels Black defendants as high-risk at significantly higher rates than white defendants. This is not speculation but documented pattern. The algorithm learned from historical arrest and conviction data that itself reflects discriminatory policing and sentencing. The AI then reproduces that discrimination at scale, affecting bail decisions and sentencing recommendations for thousands of individuals.

Healthcare allocation demonstrates how proxy variables slip past oversight. Algorithms allocate resources based on historical spending patterns, disadvantaging communities where systemic discrimination resulted in lower investment. According to AIMultiple Research, these systems use spending as a proxy for health needs, producing systematically biased outcomes where Black patients receive fewer resources than white patients with identical health conditions. The algorithm treats past discrimination as valid prediction of future need.

Hiring systems screen resumes using patterns learned from past decisions, perpetuating whatever biases shaped those earlier choices. When a company’s historical hiring favored certain demographics, the AI learns to prioritize similar candidates. Documented cases show systems de-prioritizing women through language pattern recognition—the algorithm noticed that successful candidates in the training data used certain terms more frequently, then penalized resumes containing language more common among women applicants.

The Hidden Role of Proxy Variables

Financial systems favor stable employment and education records—data points correlating strongly with existing wealth—effectively excluding talented individuals from less privileged backgrounds. Credit scoring models do not explicitly discriminate by race or class, but they achieve similar outcomes by using variables that serve as proxies. Geographic location operates the same way. Zip codes serve as proxies for race and class, avoiding explicit discrimination while producing identical exclusionary outcomes.

When AI denies loans to people in specific neighborhoods, fewer loans get approved there, shrinking data diversity and reinforcing bias in subsequent iterations. The feedback loop compounds over time. You might notice a pattern here: each round of biased decisions creates training data that makes the next round even more biased. That’s not a bug in the system—it’s how the system learns.

Why Current Mitigation Efforts Fall Short

The current conversation around AI bias reads like examining a book by looking at just two pages. Organizations concentrate on race and gender while overlooking socioeconomic status, geography, age, and linguistic dimensions. According to ISACA, this narrow focus allows consequential biases to operate invisibly, affecting credit access, healthcare allocation, and professional opportunities without triggering the oversight mechanisms organizations have implemented.

Research from Penn State found that study participants only began noticing social bias when AI showed explicitly different treatment of groups, missing more subtle patterns embedded in training data. This inability to recognize bias means organizations cannot rely on end-user feedback alone. The patterns that cause the most harm often operate below the threshold of casual observation. Systematic evaluation processes before deployment prove essential because human oversight fails to catch what humans cannot see.

A common pattern looks like this: a company deploys an AI hiring tool, runs it for six months, and only discovers bias when a journalist analyzes outcomes by demographic group. By then, hundreds of qualified candidates have been screened out based on patterns the internal team never thought to check. The harm is done before anyone noticed the problem.

Industry response remains limited and inconsistent. While AI companies attempt to address racial and gender biases by improving training methodologies and calling for diverse workforces, these efforts face pushback as companies scale back diversity initiatives. The Pew Research Center documents this retreat even as concern about AI bias grows among both experts and the public.

Some jurisdictions like New York City legally require algorithmic audits before hiring tools can be deployed, but these mandates raise new questions about measurement standards and what constitutes fair algorithmic design. Unlike human recruiters, AI algorithms can theoretically be audited before deployment—yet experts disagree on methodology and thresholds that constitute acceptable fairness across different application contexts.

Early approaches treated bias mitigation as a pre-launch checklist, but experience demonstrates that algorithmic systems drift over time as they encounter new data. Organizations treating bias mitigation as a compliance checklist rather than ongoing commitment risk systems becoming progressively less fair over time. The one-time audit provides a snapshot, but deployed systems evolve in ways that initial testing cannot predict.

Practical Steps for Leaders Deploying AI Systems

Before deploying AI in consequential domains, require comprehensive bias audits that extend beyond race and gender. These audits must examine socioeconomic dimensions, geographic and cultural factors, age-related patterns, linguistic diversity, and intersectional effects where multiple identities compound. The question to ask: Have we tested this system for bias across all dimensions that matter to stakeholders this decision affects? If the answer is no, deployment should wait.

Implement continuous monitoring rather than one-time evaluation. Establish regular review cycles examining whether deployed systems show bias drift, where feedback loops may be amplifying initial patterns, and whether outcomes match stated values. This monitoring cannot be passive. It requires active investigation of whether the system treats different groups fairly and whether that fairness holds over time as the system encounters new data.

Assign clear accountability for ongoing assessment. Make this a primary organizational responsibility with executive visibility, not a technical team’s side project. When bias monitoring lives in the margins of someone’s job description, it gets deprioritized under pressure. Executive accountability ensures that ethical AI receives the attention it requires.

Build organizational AI literacy systematically. Leaders need sufficient understanding to recognize when systems may perpetuate injustice, what questions to ask about algorithmic decision-making, and when to pause deployment pending deeper evaluation. The literacy gap is substantial—88% of non-users remain unclear how generative AI will impact their lives, even as AI makes increasingly consequential decisions about employment, credit, healthcare, and justice. Organizations cannot afford this knowledge gap among decision-makers who approve AI deployment.

Avoid common mistakes that undermine ethical AI. Do not assume algorithmic objectivity. Do not believe vendor claims of fairness without independent verification. Do not delegate all responsibility to technical teams without ensuring broader organizational competence in AI ethics. These errors stem from treating AI as a black box rather than a system requiring ongoing governance. For more on building this governance capacity, see our guide to ethical AI governance.

Engaging Affected Communities

Include stakeholders in system design and evaluation. Those most impacted by algorithmic decisions often possess insight that homogeneous development teams lack. This is not about checking a box but about accessing knowledge that improves system design and catches problems before deployment.

Make engagement substantive, not performative consultation. Include communities in decisions about whether to deploy AI in specific contexts, what fairness means in particular applications, and what outcomes warrant system modification or removal. When engagement is genuine, it surfaces concerns that internal review missed and builds trust that serves long-term organizational interests.

Consider transparency as both practice and principle. Provide stakeholders meaningful information about how algorithmic systems affect decisions impacting them. This transparency serves accountability, builds trust, and often reveals uncomfortable truths about social bias in deployed systems. When transparency uncovers problems, view this as opportunity for correction rather than reputation threat.

The Path Forward for Equitable AI

Organizations and regulators increasingly recognize the need for comprehensive bias awareness extending beyond race and gender to encompass socioeconomic status, geographic and cultural context, age, linguistic diversity, and intersectional identities where multiple dimensions compound. This shift reflects growing understanding that ethical AI demands valuing diversity in every sense rather than checking boxes on headline categories alone.

The regulatory landscape evolves unevenly across jurisdictions. While some regions implement mandatory algorithmic auditing requirements, the patchwork creates complexity for organizations operating across multiple areas. The trend suggests movement toward greater regulation, but specific frameworks remain in flux. Leaders must navigate this uncertainty while maintaining commitment to fairness regardless of what local law requires. For practical approaches to this challenge, explore how to move beyond compliance thinking in AI ethics.

Technical development continues on strategies including diversifying data sources beyond narrow population segments, employing fairness techniques such as reweighting data or adjusting model thresholds, and developing methods for measuring intersectional bias. Yet these technical solutions remain nascent, with limited peer-reviewed evidence on which approaches most effectively reduce social bias across different application domains.

Significant knowledge gaps require research attention. Limited longitudinal data tracks how biases evolve in deployed systems over months and years. Methodologies for measuring and mitigating intersectional bias remain underdeveloped. Sparse peer-reviewed evidence exists on which mitigation strategies most effectively reduce bias across different contexts. These gaps mean organizations deploying AI today operate with incomplete knowledge about long-term impacts.

Investment in organizational capacity represents a priority as recognition grows that most users cannot independently identify social bias even in training data. Technical teams alone cannot shoulder responsibility for ethical AI. Success requires diverse perspectives, continuous vigilance, and willingness to pause or remove systems that fail fairness standards. The fundamental challenge is ensuring that technological adoption serves integrity rather than inadvertently perpetuating injustice under the guise of innovation.

Why Social Bias in AI Matters

Social bias in AI matters because these systems make decisions affecting economic opportunity, health outcomes, and liberty itself. When algorithms encode historical discrimination, they perpetuate injustice at scale with mechanical efficiency. The stakes extend beyond individual harm to organizational reputation, stakeholder trust, and the basic question of whether technology serves human flourishing or undermines it. Organizations that fail to address social bias in AI systems risk not just legal liability but the erosion of the trust necessary for long-term sustainability.

Conclusion

Social bias in AI systems reflects a systemic challenge where algorithms trained on historical data encode and amplify existing inequalities across criminal justice, healthcare, hiring, and financial services. Despite 51% of people believing AI will reduce bias, evidence demonstrates the opposite—these systems predominantly reinforce discrimination unless organizations implement comprehensive auditing and continuous monitoring.

Leaders cannot delegate ethical AI to technical teams alone. Responsible deployment requires organizational literacy, engagement with affected communities, and evaluation across all bias dimensions—not just the headline categories of race and gender. For deeper exploration of these leadership challenges, see our analysis of AI bias as a business ethics challenge.

Before deploying AI in consequential domains, ask whether your organization possesses the capacity, commitment, and competence to ensure these systems serve justice rather than automate historical patterns of exclusion. The choice is not whether AI will shape society, but whether we will shape AI to reflect our values. That choice requires discernment, accountability, and the courage to pause when systems fail to meet the standards integrity demands.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is social bias in AI systems?

Social bias in AI is systematic algorithmic discrimination that produces outcomes disadvantaging specific demographic groups based on race, gender, age, socioeconomic status, or geography through patterns learned from historical data.

How do AI systems learn and perpetuate social bias?

AI algorithms learn patterns from historical data reflecting centuries of inequality, then encode these discriminatory patterns into decisions. When training data contains biased content, these biases transfer directly into AI outputs with mechanical efficiency.

What is the difference between explicit and proxy discrimination in AI?

Explicit discrimination directly targets demographic groups, while proxy discrimination uses variables like zip codes or spending patterns that correlate with protected characteristics, achieving similar exclusionary outcomes without obvious bias markers.

Why can’t most users detect AI bias in systems?

Research shows users only notice social bias when AI shows explicitly different treatment of groups, missing subtle patterns embedded in training data that cause systematic disadvantage below the threshold of casual observation.

How does feedback loop amplification work in biased AI systems?

When AI systems make biased decisions, they create data patterns that reinforce and compound that bias in subsequent iterations, making each round of decisions progressively more discriminatory over time unless actively monitored.

What steps should leaders take before deploying AI in consequential decisions?

Leaders must require comprehensive bias audits beyond race and gender, implement continuous monitoring systems, assign clear executive accountability, build organizational AI literacy, and engage affected communities in meaningful evaluation processes.

Sources

- AIMultiple Research – Comprehensive analysis of AI bias mechanisms, real-world examples across domains including criminal justice and healthcare, and economic consequences for individuals and organizations

- ISACA – Expert perspective on overlooked dimensions of AI bias including socioeconomic status, geography, age, and linguistic diversity, with analysis of feedback loops and mitigation approaches

- Pew Research Center – Survey data on concern levels regarding AI bias among experts and the public, industry responses to bias, and ongoing debates

- MIT Sloan – Analysis of pre-deployment algorithmic auditing practices and challenges in measuring discrimination

- Penn State – Research findings on user capacity to detect bias in AI systems and training data

- National University – Statistical data on public understanding and perceptions of AI’s impact on bias and discrimination